Do Pointless Things

Years ago, after a bout with burnout, I was taking extended time off to recover. I had written down a “freedom list” of things I wanted to do. One of them was to get back into drawing. I used to draw as a kid, and I was pretty good at it, but I never pursued it because… well… my parents didn’t really encourage that kind of thing. All that really mattered was my grades. So, I dropped it.

When I picked up drawing again as an adult, I decided that not only was I going to draw, but I was going to get great at drawing. This led me to buy a ton of instructional books—figure drawing, perspective, light and shading, posing. The stack was quite tall.

Before long, I hated drawing. I hated everything I made. I felt they were not good enough, and that the human figures I drew were never accurate. (This is a common outcome with adults—we push ourselves and judge ourselves way too harshly, even with our hobbies.)

I complained to my friend about how I hated my art. He offered a suggestion. He said my problem was I was trying to draw people , and we tend to have a really strong idea of how people look. It’s in our genes to see even the most subtle things that are “off” with a drawing of a person. Instead, he said, I should draw made-up animals. That way, I can’t draw them wrong, because there’s no “right” way to draw a made-up animal.

I wasn’t sure if it was the best or the dumbest idea I had ever heard. I tried it anyway.

I started sketching random animals. I let my hand do the thinking for me. One by one, wacky and colorful animals appeared before me.

I was having fun! I loved drawing again.

There was no goal to it. I didn’t know if drawing these silly animals would ever lead to anything. But I did it anyway, because it was fun.

Fast forward to a few years later: I had been writing online for several years, had grown my newsletter, but I wanted to work on a bigger, meatier project.

I decided to write a book.

I signed up for a program called Writing in Community, in which you’re supposed to write every single day, share a bit of writing in the forums, and then publish a book after six months. It seemed wild and ambitious, but I signed up anyway.

On the first day of the program, you had to write down the goal of your book. I had this idea of expanding upon my Polymath Playbook article (about the virtues of being a generalist), to share a set of tips on how to be multi-disciplinary without losing your mind.

I wrote out a few sentences describing the book. But I found myself struggling to get excited about it. I thought, “Man, if even I’m not excited about this, how will I get readers to be?”

I looked over at the corner of my desk where my iPad sat. I opened it and looked at some of the sketches of silly animals I had made. I smiled. I thought, “I wonder what their story is? What’s their life like?”

Exploring the stories of the silly animals felt like a far more interesting adventure than the polymath book idea. So I deleted the polymath summary, and replaced it with a short bit about making up animal stories for adults, inspired by The Little Prince. That’s all I had to go on, but turns out it was enough.

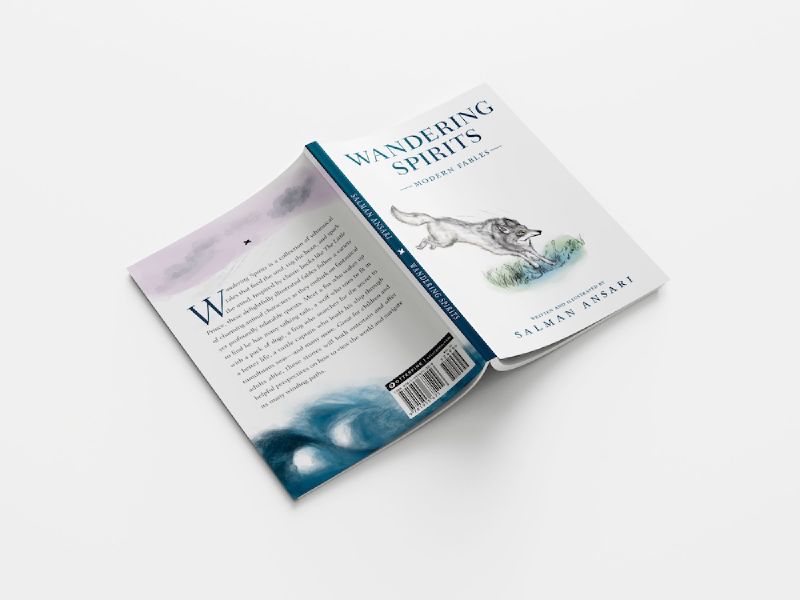

Day by day, the fables were born. A year later, I had finished the stories. A year after that, I was done editing. And then, after six months of illustration work, Wandering Spirits was published.

There’s no way I could have known that drawing silly animals would lead me to write that book.

The point of doing pointless things is that you don’t know the point.

You can’t predict it. It might pay off right away, or years from now, or never at all. But you do it anyway, because it’s fun, or because it’s satisfying some tiny curiosity in you, or just because you can.

I’ve been taking some watercolor painting classes, and one of the lessons is about using salt. Normally, I would have researched salt, understood the chemistry behind it, and planned techniques around how to best use it. I tend to overthink these things. So it was great that in the class, she just gave us some salt, and basically said, “Go nuts.”

And so I did. I painted a fox, threw some salt on it, and sat there giggling as I saw the results. I love the way it sparkles against the light. I kept the playful energy going and turned it into a silly video. Don’t be afraid to get salty, friends!

It’s hard to let yourself do things without a reason. There’s always a voice asking, “What it will lead to?” (Usually, that voice is our parents.)

But we need to silence that criticism in order to let our creativity flow. We need to give ourselves permission to play.

The capitalist pressure of purpose is all-pervasive. Escaping it is an act of rebellion.

Give yourself permission…

To write words no one will read,

To draw pictures no one will see,

To make things no one will touch.

Creativity has many goals. Consumption is only one of them.