American Traffic Crisis: The Cost of Cars

What do guns and cars have in common? They’re both privileges that are available to almost every American who can afford one. They’re also tools of murder. Every year, for the past three years, more than 40,000 Americans died in traffic fatalities.

For the individual benefit of feeling secure in one’s mobile metal fortress, we pay an incredibly heavy cost as a society. The pattern we see across both gun violence and vehicle related deaths is that American policies value individual freedoms over the safety of its collective people. Sadly, the tragic loss of lives is not the only cost we pay for this policy.

Time & Productivity: A recent study by INRIX showed that “Americans lost an average of 97 hours a year due to congestion, costing them nearly $87 billion in 2018, an average of $1,348 per driver.” In an era of increasing pressure on our time and attention, this is an enormous price to pay. With more congested regions such as the Bay Area, it is considered a good thing to have a commute of only 30 minutes each way. We have come to accept this cost as normal, and as a consequence have normalized spending less time with our friends, our families, and getting enough sleep.

Cognitive Impact: The term “road rage” was coined purely to recognize the emotional impact of being stuck in congested traffic. People have to release this anxiety somewhere, and it often ends up being projected onto coworkers, friends, and family. Additionally, there is evidence supporting the theory that air pollution causes negative impacts to our cognitive functions.

Wasted Space: To facilitate people being able to drive everywhere, we have to build parking lots at every single destination. Given that most parking lots are never full, this is an incredible waste. By reducing the need for parking, cities would immediately benefit from a surplus of space that could be used for a variety of purposes (housing, parks, pedestrian and bike pathways just to name a few).

Highways: A big part of owning and driving cars is having access to highways. The cost of building and maintaining them is placed upon all residents (through their tax dollars), regardless of whether they use them. This creates an imbalanced comparison of how much we have to pay for other forms of transportation (such as public transit). Often, we only look at the new costs of a public transit measure, without considering all the existing costs we already pay for the plethora of roads and highways we have today.

We’re not just paying for routine maintenance, either. Many of the roads and highways were built more than 50 years ago, and their planned lifetime is coming to end. The debt of our road investments is now due, and it is quite a doozy.

How much will it cost to rebuild these highways, and to expand them to accommodate increases in traffic? Robert W. Poole Jr., a transportation expert at the Reason Foundation, estimates that it will take roughly $1 trillion. Others have estimated that reconstruction and modernization could cost as much as $3 trillion. —Slate

Beyond the enormous financial burden, highways literally split cities in two and tear communities apart in the process. Not all residents are impacted equally – highways were historically used to deliberately splice and disempower communities of color (see the Atlantic piece on the role of highways in American poverty for more).

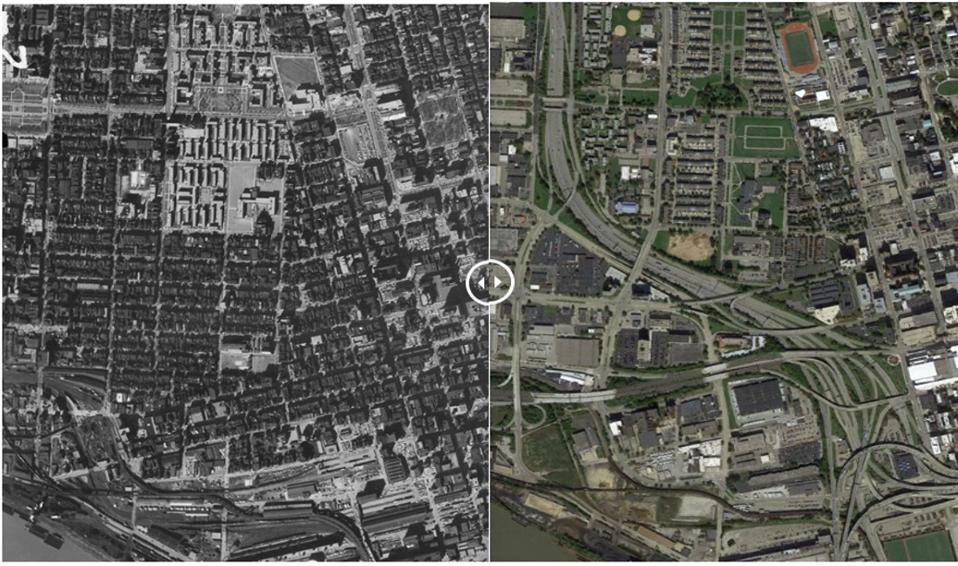

Population loss wasn’t the only result of highways running through the cores of cities. Entire neighborhoods were razed to make room for highways, destroying homes, businesses, and urban amenities. The pictures below show portions of downtown Cincinnati before (left) and after I-75. The homes and businesses on the left were largely replaced by the highway and parking lots. –Forbes

Ultimately, the biggest challenge with highways is not just their cost, but that they simply do not scale. They were never designed to meet the needs we have for them today. In fact, when the Interstate Highway was first introduced in the 1950s, the only goal it had was to ensure we had sufficient “military readiness”. Effectively, we traded healthy urban communities so that tanks could quickly get around the country.

President Dwight Eisenhower, fresh off his time as supreme commander of the Allied Forces during World War II, had seen firsthand how the German autobahns enabled the German military to move quickly over land. This experience, coupled with his participation in a 1919 military convoy that crossed the United States by land from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco, convinced him that a system of high-speed roads was necessary for military readiness. He supported federal funding for the highway system and in 1956 he signed the Federal Aid Highway Act, which secured 90% federal funding for the interstate highway system. States were responsible for the other 10%. —Forbes

The irony of it all is that if there really was an emergency that required a military vehicle to quickly cross the states using highways, it’s almost certain they would fail their mission. What happens when a soldier has to radio their general to let them know they can’t make it to the front because of a traffic jam?

Climate Change: The greatest consequence of all is the long term impact of carbon emissions to our global climate. It’s no secret that transportation is the biggest contributor to the problem:

Even as the United States has reduced carbon dioxide emissions from its electric grid, largely by switching from coal power to less-polluting natural gas , emissions from transportation have remained stubbornly high. The bulk of those emissions, nearly 60 percent, come from the country’s 250 million passenger cars, S.U.V.s and pickup trucks, according to the EPA. Freight trucks contribute an additional 23 percent. —NY Times

The latest report on climate change was incredibly bleak, and reiterated a fact most of us know, but not all of us have accepted: We are already out of time. The only battle left to fight, at this stage, is one of mitigation.

Looking at all the evidence, the case for action seems clear. This begs the question: What are our transportation planners doing to address this crisis? Unfortunately, while I’m sure their intentions are good, most are either maintaining the status quo or making things worse. There are two main reasons for this:

- An Empty Road Is Not Success: A foundational problem today is that highways (and the transportation planners that design them) are measured based on congestion, but in the opposite scale than what is actually needed. If a highway is found to have very little volume, it is given an excellent grade. By contrast, if it is used constantly and is highly congested, it is given a poor grade. Intuitively, this may make sense at first, but ultimately the measurement system incentivizes us to build and maintain highways that are never used, which don’t pay for themselves. This further exacerbates the financial tax burden on the population, while preventing investments in more scalable transportation solutions.

- Adding Lanes Eventually Increases Traffic: There is a long-standing belief that in order to cure a congested highway, we need to add additional lanes. This continues to be the case, despite evidence proving that adding lanes only increases traffic congestion in the long term. A recent paper published by the Transportation Research Record found that for every 1% increase in highway capacity, traffic increases up 1.1% in the long term. At this point, it’s become a running joke.

I realize I’ve painted a pretty dark picture of transportation and its impact on our climate. Still, there is room for optimism. Some agencies have begun to recognize their failure to measure and respond to congestion correctly, and are taking action. Regardless of how we address the cost of cars, ultimately we must accept that a problem of this magnitude warrants significant action.

In a future post, I’m planning to explore some potential solutions to this problem such as public mass transit, as well as some of the alternative transportation solutions that have come into play in the past decade (such as ride sharing, scooters, and electric cars).